selected articles & essays

Waiting Room

In March, when all but the most pressing surgical procedures ground to a halt to save staff and precious supplies for the fight against covid-19, operating suites across the country became nearly unrecognizable. At one hospital in Boston, where I live and work, more than 40 operating rooms went dark, 25 of them stripped of ventilators and other equipment — like oysters that had been shucked and devoured.

The operating rooms that remained open were reserved for urgent needs. Amber Anderson, for instance, showed up to her local emergency department in April with a throbbing pain in her side. Tests showed her urine was infected and obstructed by kidney stones, a combination that could make her very sick. Pandemic or no pandemic, she needed treatment, and a surgeon promptly threaded stents — flexible plastic tubes roughly the size and firmness of al dente spaghetti — up her urinary tract to bypass the blockages, draining pus from both kidneys.

Medicine’s Innovation Problem

The tongue-in-cheek adage “tradition unimpeded by progress” has always seemed to contain a kernel of truth when applied to health care. Historically, change has not been our medical system’s strong suit. But as COVID-19 sweeps across the nation, wreaking havoc on society and placing unprecedented strain on healthcare infrastructure, the need for system-wide innovation becomes more critical than ever.

Innovation doesn’t just refer to the race to develop a vaccine, or even the scramble to rig ventilators for multi-patient use, repurpose ships into hospitals, and fashion protective masks out of home supplies, as important as these extraordinary efforts may be. It also applies to more ordinary challenges—challenges that many hospitals were ill-prepared to face even before the current crisis.

The Burnout Crisis in American Medicine

During a recent evening on call in the hospital, I was asked to see an elderly woman with a failing kidney. She’d come in feeling weak and short of breath and had been admitted to the cardiology service because it seemed her heart wasn’t working right. Among other tests, she had been scheduled for a heart-imaging procedure the following morning; her doctors were worried that the vessels in her heart might be dangerously narrowed. But then they discovered that one of her kidneys wasn’t working, either. The ureter, a tube that drains urine from the kidney to the bladder, was blocked, and relieving the blockage would require minor surgery. This presented a dilemma. Her planned heart-imaging test would require contrast dye, which could only be given if her kidney function was restored—but surgery with a damaged heart was risky.

The New Yorker

Why Gendered Medicine Can Be Good Medicine

In January of 2005, at a conference sponsored by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Lawrence Summers, then the president of Harvard, sought to address the lack of tenured female faculty in university science departments. After promising to “provoke” his audience, Summers said that a discrepancy in “intrinsic aptitude” between men and women—a biological asymmetry—might be partly to blame. At the time, I was a pre-med student at Harvard, majoring in biochemistry. Surrounded by brilliant women in my classes and in the lab, I didn’t place much weight on Summers’s remarks. But, in the debates that ensued, it occurred to me that, beyond the basics, I wasn’t actually familiar with the biological differences between women and men—and I suspected that many of my colleagues weren’t, either. Sex and gender (the former refers to biology, the latter to social attitudes and behaviors) were rarely discussed in the context of scientific research.

The Health-Care Industry’s Relationship Problems

When I became a doctor, last year, I had to sign up for health insurance. The hospital where I work offered two primary options, a Value plan and a Plus plan. One cost less up front, while the other promised more benefits. I didn’t know which to choose; after factoring in co-pays, deductibles, and variations in coverage across networks of doctors, it wasn’t clear which would be more economical. Ultimately, I enrolled in the Plus plan, the product of guesswork more than reason.

Can Selling Insurance to Patients Transform Health Care?

On the sixth floor of the historic Puck Building, in SoHo, are the headquarters of Oscar, a two-year-old startup that sells health insurance to individuals. The office, like the building’s Shakespearean namesake, has a certain playfulness: the walls double as chalkboards, kegs of beer round out the kitchen, and the names of the conference rooms refer to famous Oscars, including one called Bluth, after the “Arrested Development” character.

Can Providers and Insurers Team Up to Fix Health Insurance?

“In health care, the days of business as usual are over.” So began an essay, published two years ago in the Harvard Business Review, by Michael Porter, a professor at Harvard Business School, and Thomas Lee, a physician. The two were proposing a new strategy centered on value-based health care—the concept of linking payment to the outcomes achieved, relative to costs, rather than to the volume of services provided.

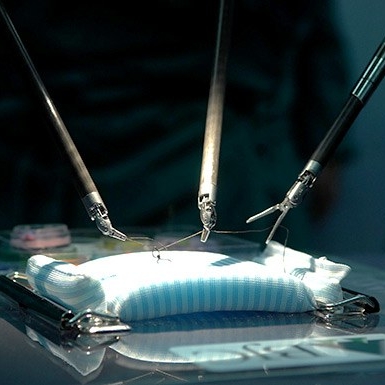

Dr. Roboto

In medical school, I watched a robot remove a woman’s uterus. The machine reminded me of a spider, but its arms held scissors, forceps, and a tissue grasper. The surgeon operating the machine made a few centimetre-long incisions in the patient’s skin and placed the instruments, along with a small camera, inside her body. Then, she moved to the other side of the room and controlled the robot’s movements using a video-game-like console. To my untrained eye, it was like watching science fiction.

The Doctor Will See You Onscreen

One night last summer, when I was working as a medical student in an emergency room, a woman pulled me aside. Her left eye was pink and looked painfully irritated. She had been waiting for hours to get it checked but would have to leave soon to catch a train home. How much longer, she asked, before she could be seen?

A doctor was able to evaluate the patient before she dashed out the door, but her dilemma struck me. We buy groceries, trade stocks, and chat with friends across the globe without getting out of bed. Yet seeing a doctor remains a fantastically old-fashioned routine: minutes of medical attention can cost hours spent in transit or in a waiting room. When the price of losing that time gets too high, we might not even bother to be seen.